With autumn waning into winter, the days of #HotNerdFall are fading away. In recognition of this, I wanted to compile and expand upon the tweet threads I started back in September. This was a series I entitled: The Hot Nerd in the Popular Imagination

Search “hot nerd girl” on the internet and you will get countless images like this of women in workout pants and crop tops.

What is “nerdy” about such women? After all, normally there is tension between nerd and jock, between a life of the mind and attention to the bodily form. What makes this apparent gym goer ostensibly a nerd? Glasses. Glasses, it seems, are the universal signifier, and only visual constant, in all images of hot nerd girls. Indeed, clothes are not, and cannot be, the signifier, since even in porn, the category “nerd” will yield you a lot of naked women, but all have glasses on.

What is “nerdy” about such women? After all, normally there is tension between nerd and jock, between a life of the mind and attention to the bodily form. What makes this apparent gym goer ostensibly a nerd? Glasses. Glasses, it seems, are the universal signifier, and only visual constant, in all images of hot nerd girls. Indeed, clothes are not, and cannot be, the signifier, since even in porn, the category “nerd” will yield you a lot of naked women, but all have glasses on.

There are not, it seems, any actual activities that universally signify nerd-dom. Not being on a computer, or holding books, though these tropes do commonly appear. Hot nerdness, then, is not dependent on a particular behavior; many hot nerds on the internet are, in fact, doing nothing at all, unless you count gazing suggestively at the camera as an activity.

If, in fact, glasses make the nerd, what makes the nerd hot? Laying aside for now the prerequisites to hotness enforced by the culture (whiteness, thinness), it appears that hot nerds often wear glasses, but do not look through them.

The coy, indirect gaze is not hot nerd specific. It’s common across sexy pics of women of all genres, and has been seemingly forever–old timey women peep over the edge of a paper fan in engravings and drawings, never looking directly at a man. For the nerd, glasses are that prop.

The “looking over the glasses and biting on a pen” pose is a common one in depictions of the hot nerd girl. The irony, of course, lies in the kernel of truth in the nerd-glasses association. Nerds often do wear glasses, because they need them so desperately. Without mine, I cannot drive, or read, or even run, so altered is my depth perception.

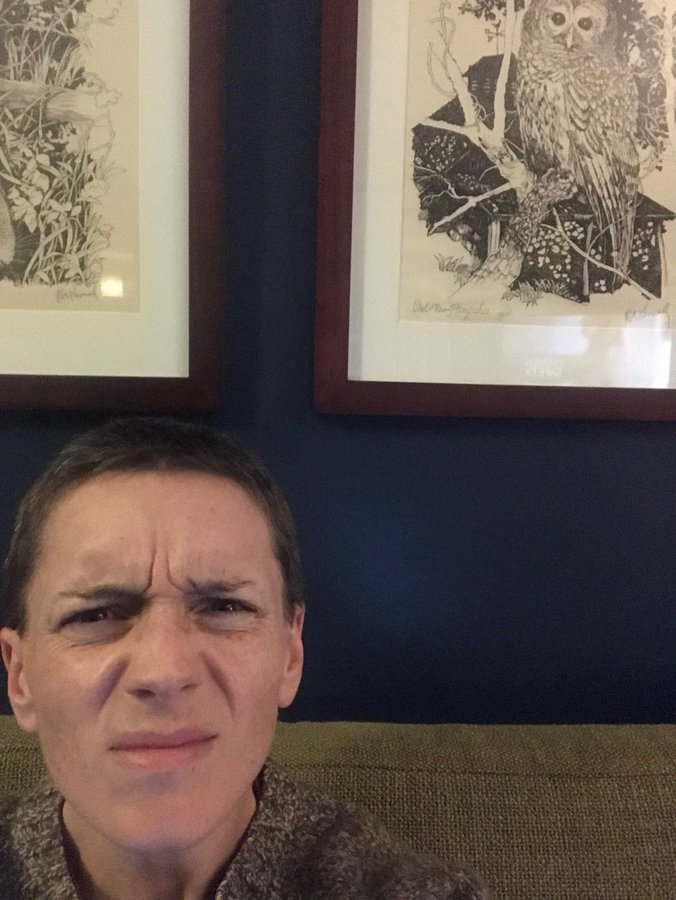

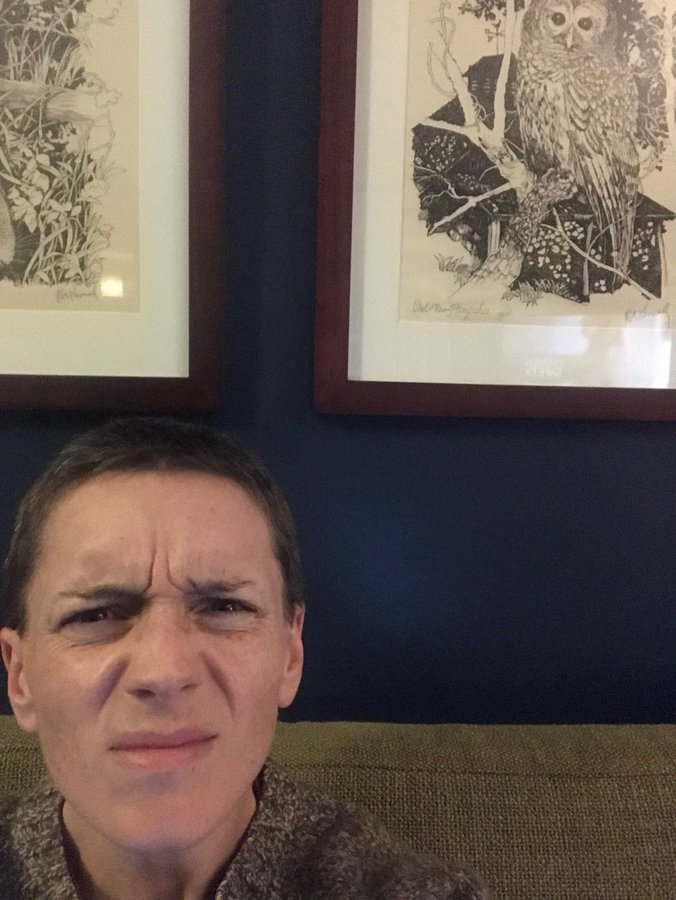

If I were to gaze up at you over my glasses from the profundity of my myopia, you would be blurry edged, maybe doubled, unless I squinted like this:

If glasses are critical to nerdness, then why are the hot nerds so often looking over them at the camera? The hot nerd in such pics has been interrupted, her attention fractured. She looks up, pen in hand, or mouth, because she’s a nerd and she was working, thinking, writing, but now she’s looking at you, because you demanded her attention, much as Dan Bacon, Dating and Relationship Expert for Men, and author of the blog post “How to Talk to a Woman Wearing Headphones” advised (you’ll need to scroll down a bit to get to the how-to bit, but it is absolutely worth it).

The interruption of focus is pertinent to interacting with nerd girls, because, after all, the nerdness of the nerd comes from an intellectual pursuit of some kind. A mind trained on an idea, or a task. Nerds at work will often look something like this, not at all interested in or aware of the camera:

photo by Kristen Covino

Would a nerd dressed in a spiked skateboard helmet, a flower bandana, and a child sized yellow rain slicker who is scowling at a spring balance in the sun ever qualify as a #hotnerd? Maybe, but hot nerds are almost invariably looking at the camera. The exceptions to that rule are instructive.

What are the constraints on HotNerdGirl behavior? She can, presumably, do slightly more than bite a pen while looking over her glasses. Stock photos indicate that she can, for instance, look at a book. But what are the rules?

If she does intend to read a book, it appears she must be just coming back from, or just about to leave for, an aerobics class. She should be having some thermoregulation challenges that warrant, for example, a combination of a hoodie or sweater, boy shorts, and leg warmers.

She must indicate, through some combination of gestures, that she is nonetheless aware of being looked at and admired. In this example, note the pointing of the toes, which signals this awareness since no person alone and unselfconsciously reading a book would adopt this posture.

If a Nerd previously deemed Hot decides to read in a posture less self-consciously hot, and does so in a wool sweater several sizes too big and a pair of jeans not ever worn outside the house, does she forfeit her hot status? When does the HotNerdGirl become merely a Nerd? In other words, if a NerdGirl reads a book without a man or a camera around to determine her hotness, is she still hot? Is hotness something bestowed by the beholder? Is hotness a state of being, or an activity? If an activity, is it a passive or an active verb?

There is another exception to the rule of needing to gaze at the camera/man for hot nerd girls, and that is the HotNerd, Gamer Phenotype. HotGamerNerdGirls, unlike other HotNerdGirls, do not have to wear glasses. I’m wearing mine here because I genuinely can’t see without them.

Let’s search the image for familiar tropes. We see workout wear (crop top, leggings): the typical attire for any HotNerdGirl not in a plaid miniskirt and knee socks. Even a cursory internet search indicates that glasses are not actually required of this phenotype. Why this privilege granted to this particular type of HotNerd? I posit that, gaming does not require the myopic intellectualism of other nerd pursuits, while still demanding the flow state/focus/withdrawal from the world that defines the nerd.

This photo took many takes to properly imitate the originals. The combination of enough bodily display, while incorporating the controller into the frame, and making a facial expression that suggests concentration, but still a self-consciousness of sexily being on display was tough. If you look at the faces of people actually immersed in a video game, they do not look self-conscious. They look like this.

The stock photos of HotGamerGirls lack this quality of immersion, which is what defines the nerd, and the subjects in the photos look like maybe they aren’t playing video games at all–like maybe the controller isn’t even connected to anything. There’s a joke in these images, like, “would you believe a girl is gaming?!” Is the girl in on it, or is it like the line in Mad Men where Freddy refers to listening to Peggy think as, “Like watching a dog play the piano.” Clearly not done well, but the very idea is astonishing.

Regardless, we have now run into the fundamental tension in the phrase “Hot Nerd.” A nerd is inward facing, consumed and concentrated, in a flow state, heedless of the regard of others. Hotness seems to require acute awareness of another’s gaze, and an attentiveness to it. Perhaps that’s where the absurdity at the heart of HotNerdGirl stock photos comes from; the incompatibility of the two modifiers. So, is it actually impossible for ANY nerd to be hot? Can that needle be threaded? Can it be threaded by women?

If you search not “hot nerd girl,” but simply “hot nerd” you will get a gender mix but not much racial diversity. Megan Thee Stallion, who originated the hashtag #HotNerdFall appears for that reason, but the images are otherwise dominated by white folks. John Oliver features prominently, and so does Chris Hayes. Most of the non-famous, stock photo HotNerd guys are well muscled, in tight fitting oxford shirts and sweater vests, thick-framed glasses settled above their aggressively angled cheekbones. The silliness, and the tension here is in our perceptions of how nerds allocate their time. The conflict lies between how much effort and hours at the gym would be needed to sculpt such a body, and the intellectual rigor that defines the nerd. Of course, we should ask ourselves, why couldn’t the toned specimen on the treadmill next to yours who is one careless flex away from tearing every seam in his clothing be listening to a recording of Hadley Wickham’s “A Layered Grammar of Graphics” or an audiobook of de Tocqueville on those earbuds?

At least for men, there might be some room for a conception of the hot nerd as one with appetites both mental and physical. Scholar-athletes, philosophical warriors, virile poets; history holds such men in high regard. But what about women?

In her essay “Women, Race, and Memory,” Toni Morrison writes, “rigorous intellect, commonly thought of a male preserve, has never been confined to men, but it has always been regarded as a masculine trait.” This seems contradictory. Male, and masculine, but not seen only in men. Where then, outside of a man, can we find rigorous intellect? Women throughout history have possessed it, but in Morrison’s construct, these women have been definitionally excluded from traditional femininity. Once a woman demonstrates fierce intelligence, she is cast outside the pale. She is, to put it another way, “not like other girls,” and is, in fact, not like a girl at all. She is engaging in men’s work, and committing a transgression.

Nerd-dom, the state of immersion, the training of a formidable intellect on an object of complete focus is inward-oriented. It is a looking-away, a loss of awareness of the body. The stock photo HotNerdGirl looking into the camera, and at the presumptive man behind it, reflects the joke at the heart of it; she can’t be a nerd and be looking at you like that. The nerdness and the hotness cannot exist in the same place and time for a woman. The amplitude of the two waves are opposite and cancel each other.

I tried to make a photo of myself in a genuine state of nerdiness. I set my camera on a timer and set it beside me while I worked so I would forget it was there and see what I look like when I am not aware of being observed. I clothed myself in the layers of corduroy and wool and fleece that I choose when I am home alone in winter, heedless of the opinions of others. But still, there was a trace in each photo that I was conscious of the lens. There was the faintest trace of a smile in all of them, that classically female social signal. I know my face at rest, alone, focused. To most people it looks mad, bitchy. But that is my flow state, my immersed intellect. It is inherently anti-social, and, it would seem, not entirely compatible with being a woman.

We are sheltering here to protect our physical bodies, and those of the rest of society. We are mitigating risk, and trading full sanity for bodily safety. It’s a fair and reasonable bargain, and my body ticks along as usual, carrying laundry, running, eating. My mind, on the other hand, is in a paradoxical retreat. Never much inclined to social interaction, it seems to want less and less of it now. The zoom meetings requested occasionally by students elicit dread for full days leading up to them. An email asking me to “please call at your earliest convenience” makes me want to crawl under a table. I don’t want to talk to anyone. I want to do strange things like watch my tomato seedlings. Their progress is imperceptible, of course, but I stare at them like you watch an infant sleep, mesmerized by the rhythm of the breathing, terrified that it might stop, believing in your magical thinking that by your vigilance you are keeping them alive. Sitting by a window, not able to answer emails, or look over student work, or do anything useful, I watch the sliding passage of the shadows my houseplants cast on the walls and floor for long stretches of lost time.

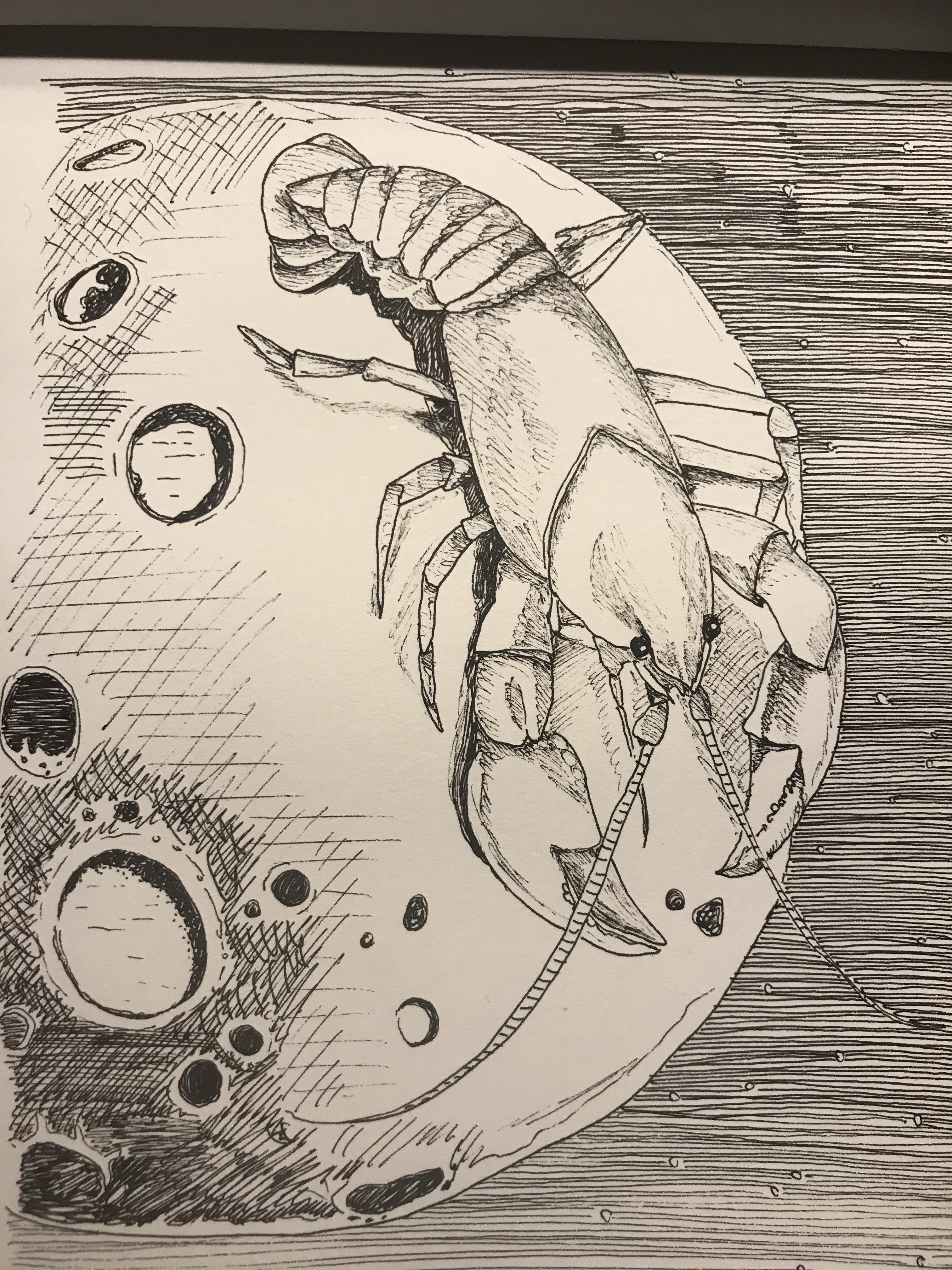

We are sheltering here to protect our physical bodies, and those of the rest of society. We are mitigating risk, and trading full sanity for bodily safety. It’s a fair and reasonable bargain, and my body ticks along as usual, carrying laundry, running, eating. My mind, on the other hand, is in a paradoxical retreat. Never much inclined to social interaction, it seems to want less and less of it now. The zoom meetings requested occasionally by students elicit dread for full days leading up to them. An email asking me to “please call at your earliest convenience” makes me want to crawl under a table. I don’t want to talk to anyone. I want to do strange things like watch my tomato seedlings. Their progress is imperceptible, of course, but I stare at them like you watch an infant sleep, mesmerized by the rhythm of the breathing, terrified that it might stop, believing in your magical thinking that by your vigilance you are keeping them alive. Sitting by a window, not able to answer emails, or look over student work, or do anything useful, I watch the sliding passage of the shadows my houseplants cast on the walls and floor for long stretches of lost time. I have the capacity for focus, just not on anything I am supposed to be doing. Overcome with anxiety and inexplicable dread at the prospect of responding to work emails, I instead sat at my dining room table for two hours drawing an oyster toadfish’s every skin fold and wrinkle. I want to spend my time among the living, but only the kinds that are indifferent to this disaster. The ones that perhaps note, in passing, some perturbation in the human nations, but have other, pressing concerns.

I have the capacity for focus, just not on anything I am supposed to be doing. Overcome with anxiety and inexplicable dread at the prospect of responding to work emails, I instead sat at my dining room table for two hours drawing an oyster toadfish’s every skin fold and wrinkle. I want to spend my time among the living, but only the kinds that are indifferent to this disaster. The ones that perhaps note, in passing, some perturbation in the human nations, but have other, pressing concerns.

A little less than a week ago, I developed symptoms consistent with COVID-19. They have been mostly mild: a transient fever, fatigue, aches, a dry cough, shortness of breath. The line between somatic and psychosomatic blurred and then disappeared as I sat on the couch one evening, and began to feel desperate for air. I stood up, trembling, staring hard at my fingernail beds for any hint of cyanosis. Panic, the only perpetual motion machine, fed on itself, its symptoms the same as those of genuine dyspnea and deadly decline. My husband asked what to do, if he should call for help. I foresaw an oxygen mask, intubation, the frantic clawing of someone in respiratory distress. I forced myself to slow my breathing, terrified more of the hospital, the last place to be if you can possibly help it, where there are too many bodies, too few beds. I pulled air into my lungs and slowly stopped trembling. There’s nothing to do but ride it out at home anyway, and I’m alright. Just tightness in my lungs, and pausing at the top of the stairs with my hands on my knees, catching my breath.

A little less than a week ago, I developed symptoms consistent with COVID-19. They have been mostly mild: a transient fever, fatigue, aches, a dry cough, shortness of breath. The line between somatic and psychosomatic blurred and then disappeared as I sat on the couch one evening, and began to feel desperate for air. I stood up, trembling, staring hard at my fingernail beds for any hint of cyanosis. Panic, the only perpetual motion machine, fed on itself, its symptoms the same as those of genuine dyspnea and deadly decline. My husband asked what to do, if he should call for help. I foresaw an oxygen mask, intubation, the frantic clawing of someone in respiratory distress. I forced myself to slow my breathing, terrified more of the hospital, the last place to be if you can possibly help it, where there are too many bodies, too few beds. I pulled air into my lungs and slowly stopped trembling. There’s nothing to do but ride it out at home anyway, and I’m alright. Just tightness in my lungs, and pausing at the top of the stairs with my hands on my knees, catching my breath.

What is “nerdy” about such women? After all, normally there is tension between nerd and jock, between a life of the mind and attention to the bodily form. What makes this apparent gym goer ostensibly a nerd? Glasses. Glasses, it seems, are the universal signifier, and only visual constant, in all images of hot nerd girls. Indeed, clothes are not, and cannot be, the signifier, since even in porn, the category “nerd” will yield you a lot of naked women, but all have glasses on.

What is “nerdy” about such women? After all, normally there is tension between nerd and jock, between a life of the mind and attention to the bodily form. What makes this apparent gym goer ostensibly a nerd? Glasses. Glasses, it seems, are the universal signifier, and only visual constant, in all images of hot nerd girls. Indeed, clothes are not, and cannot be, the signifier, since even in porn, the category “nerd” will yield you a lot of naked women, but all have glasses on.

The race course is familiar to me, and I have run and biked the route before. I got through a couple hundred yards cataloging all the times I have traversed certain sections of road, remembering particularly the time I got lost while cross country skiing and emerged from the woods five miles from home without my phone. I walked back in my boots, my skis over my shoulder as the light died and I tried not to get panicky. I could see that scene so vividly that I looked across the road at where I’d slogged in the gritted gray snow, and I nodded to my own ghost.

The race course is familiar to me, and I have run and biked the route before. I got through a couple hundred yards cataloging all the times I have traversed certain sections of road, remembering particularly the time I got lost while cross country skiing and emerged from the woods five miles from home without my phone. I walked back in my boots, my skis over my shoulder as the light died and I tried not to get panicky. I could see that scene so vividly that I looked across the road at where I’d slogged in the gritted gray snow, and I nodded to my own ghost.

There were five more stations to survey after that, and by the time I was done, it was past seven and I started back down the trail to go home. I mostly moved fast enough to keep ahead of the flies, but in the wet places the mosquitoes would rouse themselves at my passing. Their whine sometimes sounds like a suggestion of human voices, and I calibrate my time away from society by what feeling that elicits. Early in my hiking trips, the thought of engaging anyone in conversation, however briefly, fills me with tiredness, or sometimes dread. After a day away, I handle the prospect with more equanimity. Every time I mistake mosquitoes for people talking, the last line of Prufrock springs into my head, “Till human voices wake us, and we drown,” and then I puzzle over that line for a quarter mile or so.

There were five more stations to survey after that, and by the time I was done, it was past seven and I started back down the trail to go home. I mostly moved fast enough to keep ahead of the flies, but in the wet places the mosquitoes would rouse themselves at my passing. Their whine sometimes sounds like a suggestion of human voices, and I calibrate my time away from society by what feeling that elicits. Early in my hiking trips, the thought of engaging anyone in conversation, however briefly, fills me with tiredness, or sometimes dread. After a day away, I handle the prospect with more equanimity. Every time I mistake mosquitoes for people talking, the last line of Prufrock springs into my head, “Till human voices wake us, and we drown,” and then I puzzle over that line for a quarter mile or so. There isn’t much of that easy sort of trail on the Davis Path, and I was relieved to get back to the lower miles where I began to encounter people again. I could gauge my proximity to the trailhead by how dirty and tired people looked, so when I met a family, a man, a woman, and a teenager, looking utterly crisp and chipper, I knew I was almost done. The man stopped me and asked about the bugs. “Pretty bad,” I told him, and his face fell. “The moment I stopped to take in the view, I was under siege. It happened on the nice sunny ledges too.” He frowned and said, “That’s not what I read online on the trail reports. Online people said the bugs were bad on other trails but not this one.” He stared at me, and I shrugged. My face, I would discover later, was streaked with blood, and there were raised welts around my neck and along my jaw. My ears were swollen twice their normal size, their whorls and helices looking shiny and rubbery red, like a poor first attempt at balloon animals. My hat where it had been in contact with my ears was bloodstained. “I don’t know what to tell you. They are really terrible. Disfiguring, in fact,” I said to him. His wife was silent but looking more and more concerned. “Well, online no one said anything about that.” He questioned some more, and I told him where I’d been, and how long I’d been out. Finally I said, “I wish you the best, but it is the flies’ time out there. We are only interlopers.” The wife’s eyes tracked me, almost pleading, as I turned to go. As I walked away, I felt the calm surety that always comes after exhausting myself in the wilderness. Whatever that man said or thought was not my concern, and could not trouble me. I existed fully in the moment I inhabited, sore, bloodied, blistered, but with my mind at ease, neither in front of me nor behind, and with my skates fully under me now.

There isn’t much of that easy sort of trail on the Davis Path, and I was relieved to get back to the lower miles where I began to encounter people again. I could gauge my proximity to the trailhead by how dirty and tired people looked, so when I met a family, a man, a woman, and a teenager, looking utterly crisp and chipper, I knew I was almost done. The man stopped me and asked about the bugs. “Pretty bad,” I told him, and his face fell. “The moment I stopped to take in the view, I was under siege. It happened on the nice sunny ledges too.” He frowned and said, “That’s not what I read online on the trail reports. Online people said the bugs were bad on other trails but not this one.” He stared at me, and I shrugged. My face, I would discover later, was streaked with blood, and there were raised welts around my neck and along my jaw. My ears were swollen twice their normal size, their whorls and helices looking shiny and rubbery red, like a poor first attempt at balloon animals. My hat where it had been in contact with my ears was bloodstained. “I don’t know what to tell you. They are really terrible. Disfiguring, in fact,” I said to him. His wife was silent but looking more and more concerned. “Well, online no one said anything about that.” He questioned some more, and I told him where I’d been, and how long I’d been out. Finally I said, “I wish you the best, but it is the flies’ time out there. We are only interlopers.” The wife’s eyes tracked me, almost pleading, as I turned to go. As I walked away, I felt the calm surety that always comes after exhausting myself in the wilderness. Whatever that man said or thought was not my concern, and could not trouble me. I existed fully in the moment I inhabited, sore, bloodied, blistered, but with my mind at ease, neither in front of me nor behind, and with my skates fully under me now. At the shore, there were some white people, rich, generations safe and clear of any laboring past, who had given their children agrarian village names like Thatcher and Mason. The family gathered by the water, and someone tried to herd the kids who were pelting each other with rose hips. I watched three dolphins cruise by in the shallows, unnoticed.

At the shore, there were some white people, rich, generations safe and clear of any laboring past, who had given their children agrarian village names like Thatcher and Mason. The family gathered by the water, and someone tried to herd the kids who were pelting each other with rose hips. I watched three dolphins cruise by in the shallows, unnoticed. Why does any living thing notice the things it notices? There have been studies done on shearwaters to investigate how they find their way across a featureless ocean. Suspecting it was by scent, researchers began testing this by dousing the birds’ nasal passages with zinc sulfate, which renders the birds temporarily anosmic: deprived of the ability to smell. The birds are then released and followed with tracking devices. Some activities are not impaired by the lack of smell; the birds can generally find food and gain weight, and some do eventually find their way home, even after being dropped off hundreds of miles away, but their way-finding is altered. If they are near shore, they stay close to it, using features of the coastline to orient, like a visual tapping of a white cane. Species that usually migrate at night might shift to day time travel to better see these landmarks. But many birds wander aimlessly for the duration of their scent-blindness. I think about these birds all the time, released after the rinsing, their mental maps blanked out. What is in their minds? A gray static where the knowledge used to be? An urge for home, but no idea how to begin heading back to it? Panic?

Why does any living thing notice the things it notices? There have been studies done on shearwaters to investigate how they find their way across a featureless ocean. Suspecting it was by scent, researchers began testing this by dousing the birds’ nasal passages with zinc sulfate, which renders the birds temporarily anosmic: deprived of the ability to smell. The birds are then released and followed with tracking devices. Some activities are not impaired by the lack of smell; the birds can generally find food and gain weight, and some do eventually find their way home, even after being dropped off hundreds of miles away, but their way-finding is altered. If they are near shore, they stay close to it, using features of the coastline to orient, like a visual tapping of a white cane. Species that usually migrate at night might shift to day time travel to better see these landmarks. But many birds wander aimlessly for the duration of their scent-blindness. I think about these birds all the time, released after the rinsing, their mental maps blanked out. What is in their minds? A gray static where the knowledge used to be? An urge for home, but no idea how to begin heading back to it? Panic?